By Caroline Lanni

***

[broadstreet zone=”53130″]

FRAMINGHM – As time passes, history is made. Historical findings and people are remembered by what is left behind and what story goes along with it.

To embrace these historical findings, the volunteers at the Framingham History Center designated themselves to make use of these items and discover the stories behind it all.

Established in 1888 as the Framingham Natural History and Historical Society, the Center today offers public events, lectures, exhibitions, celebrations, and tours to educate the public on Framingham’s past, present, and future.

To mark Black History Month, the the Framingham History Center presented a virtual program that highlighting the historical “People of Color” back in the 1600’s to 1800’s in Framingham, and the artifacts they left behind.

History Center Executive Director Annie Murphy said “ee had to switch up our normal format to a webinar format because we have almost 150 people signing up, so for the quality of the program this is what we need to do.”

“We have known for a quite a while that we needed to pull this history together and thanks to a grant from the Sudbury Foundation and to our good fortune in finding Mary McNeil, we are well on our way,” said Murphy.

The virtual programs have been a “wonderful way” for the History Center to share the information and stories about Framingham’s history, said Murphy.

[broadstreet zone=”58610″]

Framingham History Center Assistant Director introduced the History Center’s Stacen Goldman and McNeil, to start the Zoom event. Goldman has been the curator at the Framingham History Center for the past four years and received her MA in History with a concentration in public history from Northeastern University in 2012. Goldman has been working in the historical agencies in the greater Boston area since

2011.

“The goal of her [Goldman] work is to make people feel immersed, empowered, and emotionally invested in community history,” said Rankin.

“An engaging historical experience deepens an individual’s understanding of themselves, cultivates community and fosters social justice. She is committed to putting history into the hands of all people and is especially interested in the democratization of historical collections and imagining creative ways of engaging history through material culture,” said Rankin.

McNeil is a PHD candidate in American studies at Harvard University, and interests include, intersection of black studies, native American indigenous studies, geography, social history, and black and indigenous feminism. Her dissertation examines black and native claims based in Boston and surrounding areas, during the Black Power and Red Power area, Rankin added.

“Mary’s research has been supported by the Harvard University Native American Program, The Mellon Foundation, The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, and the Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History,” Rankin added. “In addition to serving as the [FHC] scholar and resident, Mary is also a research assistant for the African American Trail Project at Tufts University, Mary was born in Louisville

Kentucky, and is a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe.”

“I would like to acknowledge I am speaking to you from land, that is the ancestral territory of the Nipmuc and that the Framingham History Center also stands on the land of the Nipmuc,” said Goldman. “Mary is speaking with us today from the ancestral territory of the Massachusetts people.”

[broadstreet zone=”59946″]

The Framingham History Center is acknowledging and honoring traditions of all people indigenous, to what is currently known as the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, said Goldman. “Such as, The Nipmuc of Massachusetts, The Chappaquiddick, Paniquuk, quantuck, Maheekin, Nosit, and Wampanoag.”

Goldman told a story about how she came across an article about the Fuller School of Framingham and how they [The Fullers] were the first black people integrated in Framingham.

“This gave me pause,” said Goldman, since she knew there were Black people in Framingham before the Fullers came. [Like the Benson Family]. “What really got me,” was when she pulled this article from the folder it was next to old newspaper copies from 1913 – 1914 written by a black man about the black community that was centered by a Church.

Goldman added, it turns out that this community was formed before the Fullers came to Framingham and what shocked Goldman was that they had two years of newspapers that were buried in their archives.

“Their names became hidden – waiting to be discovered,” said Goldman.

Since their collections have these hidden gems of history, they realized at the Framingham History Center they needed to get someone to organize and find these gems in their collections, said Goldman.

[broadstreet zone=”59983″]

“We are starting at the beginning with some of our oldest materials, which is why we are starting with 1600 to 1800,” said Goldman. ““Thanks to a grant from the Sudbury Foundation – we were able to fund an initial round of scholarship with Mary McNeil, who has been working in our collection and finding incredible treasures and working with them.”

“These are stories that were really span borders,” she said.

“I come to this work because I have a really strong belief that the past is usable,” said McNeil. “It is really important to be grounded in and the understanding of the historical prophecies that lead up to this moment.”

It is important to look at our ancestors and what rights they had to fight for and “the field of history is so important,” she added.

“I come to public history through the mentorship of some wonderful professors at Tufts University. I began to work with them as a research assistant for the African American Trail Project,” said McNeil. ““I learned so much – through public history so many questions have opened up and I find myself moving further and further back in history and now I am in the 17th Century.”

McNeil said “I hope with this public humanity – that it creates a space of collaboration and – a service of better futures.”

Goldman asked the question to McNeil about “finding aids,” and why it is important.

McNeil said finding aids are a record or a catalog that spells out the information in more detail about a collection.

[broadstreet zone=”54526″]

“It is helpful for researchers who are in traditional academic settings such as me, and for folks who are interested in doing family history, – the goal with this finding aid is to get the word out that this is what it is and that it is here for you to look at.”

Goldman said there are “cross-collection finding aids,” that they are working on as well. These are associated with this specific time period about native people, and all different kinds of people in Framingham, who are not white.

McNeil said, developing “cross-collection finding aids” are important because the vast majority of papers in their collections are about wealthy white families, “so when you’re looking at the collections you are looking for traces of folks.”

It is a fragmented story, and it is important to put the pieces together to connect and find people from back then, said McNeil.

“It is painful and sad” – to find folks and only to see those references of them as bills of sale or the people who enslaved them – “from those little fragments you can build out much larger stories,” said McNeil.

As a researcher, trying to find these people, where do you start? said Goldman.

McNeil said you begin with what has already been written about and look at secondary literature with people who wrote about the area.

“Names are so important, it’s really important to look at the secondary sources and try and get names you might start looking for in a finding aid,” said McNeil.

Some more recent and some being “quite old,” she added.

“To get the lay of the land is important and then looking for what is more a critical scholarship – with a lot of the work from this aid, this is how I began,” McNeil said.

Goldman said, “We are offering voices back to people who don’t have voices in those sources.”

How did you know what you wanted to look at in our collection? said Goldman.

McNeil said you are going to find new things when you enter an archive.

McNeil added, “You go in with your names and your ideas” then as you continue, “it is kind of like going down a rabbit hole.”

“I am a nerd for maps, and I am very interested in maps,” she added. Scholars have said, “They [the maps] are crucial technologies of empire. … Maps inform us of “colonial thinking” and who belongs and who does not.

“My general process is looking for names, secondary names, specific places, and certain types of documents that have historically yielded a lot of information about what is going on at a particular place and time,” said McNeil.

Goldman said to McNeil, “You requested to see items that I didn’t even know we’ve had until you asked for them.”

Goldman added that her [McNeil] outside perspective is important and brings a new perspective of pieces to look at, which is great.

When you hit roadblocks how do you work around them? asked Goldman.

“I think it is inevitable when you’re trying to learn more about black and native folks in the 16th Century in a colonial archive that you’re going to hit roadblocks, and I think it is important to accept and acknowledge that it is okay,” said McNeil. “These archives are a reflection of a particular way that black and native life was valued, so there not complete records.”

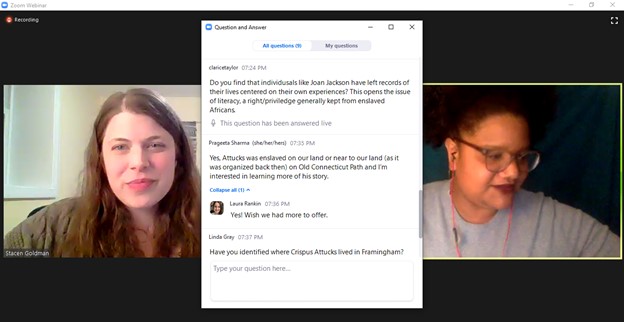

McNeil learned here at the Framingham History Center that Crispus Attucks’s mother descended from someone who is from Natick and many stories on his family about where they came from.

“So, there are those roadblocks, and acknowledging those roadblocks are important,” said McNeil.

“History is kept alive by descendants and stories are passed down, – there will always be roadblocks and staying the course with the descendants is really important,” said the PhD canddiate.

Has anything surprised you in our collection? asked Goldman.

McNeil said she never knew what a “contested place Framingham was.”

In your wildest dreams what would you like to come across in the collection? asked Goldman.

McNeil said in her dreams she would like to find diaries.

“I would like to find more diaries and find more information about some of the women enslaved in Framingham,” said McNeil.

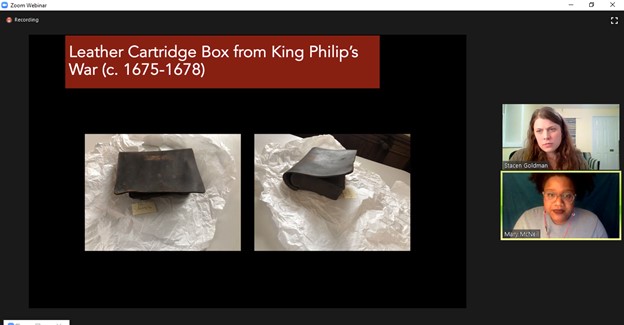

McNeil showed some specific items that they highlighted from their collection. The first item that was shown in the presentation was a leather cartridge [object 83] box from King Philip’s War [c. 1675-1678], said McNeil.

McNeil said according to the finding aid, it was donated by Eli Constance who was a descendant of Abraham Constance who fought in this war.

“I think of it as a seller’s colonial keepsake. It’s an object that has a very violent history attached to it and it is very interesting that it was the first object I saw in the collection,” she said.

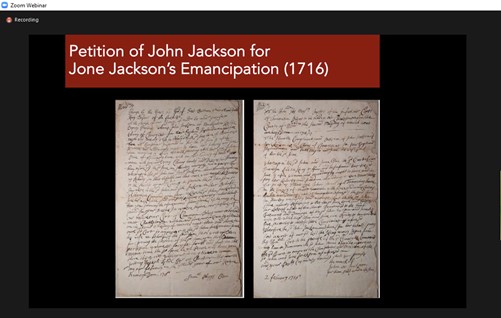

McNeil also highlighted the items, a Survey of Natick Lands Claimed by Samuel Gookin and Samuel How [1696,] Janes Bill of Sale [1743,] and a Petition of John Jackson for Jone Jackson’s Emancipation [1716].

McNeil said, “It is really easy to get overwhelmed by how sad a lot of the documents are.”

Goldman said, they will be digitizing the finding aid from the Framingham History Center and “it’s so important to see in one list the kinds of things we have.”

Rankin said their next event, “Between the Lines: Interpreting the Lives of Enslaved People in Framingham and the Royall House, on March 25 at 7 p.m. Royall House & Slave Quarters Executive Director Kyera Singleton and Framingham History Center Curator Stacen Goldman will demonstrate how one analyzes primary sources regarding enslaved people and much more.”

Individuals can register for a ticket via www.framinghamhistory.org

***

Caroline Lanni is a 2021 SOURCE intern. She is a senior at Framingham State University. Screenshots below by Lanni.

***