[broadstreet zone=”51611″]

FRAMINGHAM – Framingham made headlines electing the first popularly elected African-American woman Mayor in Massachusetts in November of 2017.

But, many in Framingham do not know of the first & only African American selectwoman elected in the Town of Framingham’s 317-year history.

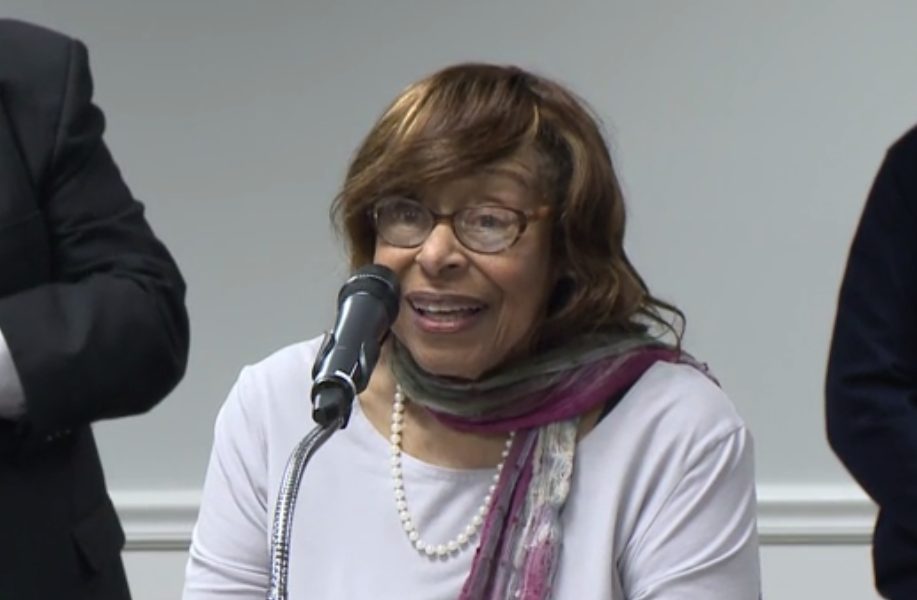

Her name is Esther A. H. Hopkins.

She served on the Board of Selectmen from 1999 to the early 2000s, even becoming the Board’s first African-American chair.

After stepping down as a Selectwoman, she became member of the Keefe Tech Regional Vocational School Committee until retiring from politics to Martha’s Vineyard with her son. She also was involved in the Framingham Finance Commission and Framingham’s Tercenntenial Celebration.

Born a few years after women were given the right to vote with the 19th amendment, Hopkins, now 93, spoke to SOURCE for this report from the island.

Hopkins earned many educational degrees and could be considered a “Hidden Figure” of science. Late in life she received a law degree, and used her scientifically and legal degrees to work for the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection.

On a day in which Framingham celebrates the women’s right to vote, it is only fitting to honor the only African-American ever elected Selectman in the Town’s 317 year history.

This is Hopkins’ story.

[broadstreet zone=”53130″]

Esther’s story starts with her mother and father. Her mother, Esther Small, migrated from South Carolina to New Rochelle, New York at the age of 12. Small was the first member of her family fully freed from slavery. She also became the first member of her family to graduate from high school and own a home. Small met her husband, George Harrison, when she was working as a chauffeur in Stamford, CT. Harrison was also employed as a chauffeur.

Esther Hopkins was born to Small and Harrison on September 18, 1926 in Stamford, CT. She had two brothers, one older and one younger.

While her family battled poverty, Esther was encouraged by her parents to pursue her love of knowledge that would define her life.

According to an article written by the Martha’s Vineyard Times about Hopkins, she said that she “because of my parents, I grew up feeling that whatever I chose to do, my parents would let me do it. I enjoyed music and they got me piano lessons. My first teacher wasn’t very good, so they got a better teacher, one that white girls had. I had a chance to go to live theater in Stamford. We were poor people, but there are always things you can do.”

Throughout middle and high school, Esther played the piano at her church. This eventually led her to meet her future husband, T. Ewell Hopkins, a Stamford minister who also eventually became a minister in Framingham. They married in 1959 and were married for 42 years until his death in 2001.

She also mentioned that, in addition to her love of music and theater, she loved spending time at the public library as well. According to the Martha’s Vineyard Times, she said that while she was intimidated at first, she knew that what she wanted was at the library, so she frequently went.

Hopkins was known as a really smart kid in her youth in Stamford, CT. At the age of 3, she started kindergarten when she passed an early enrollment test. She excelled in the classroom, particularly in the subjects of math and chemistry. She graduated from Stamford High School in 1943 and she was 21st in her graduating class. To put that in perspective, Stamford, CT at the time was overwhelmingly white with approximately 95% of its population in the 1940 Census identifying as white.

[broadstreet zone=”58610″]

Due to the family’s poverty, the family could only afford to send one of their kids to college. Small insisted that all of her kids receive a high school diploma. Her brothers were not interested in pursuing higher education once they handed their mother their high school diplomas. But, Esther Hopkins certainly was.

Hopkins sent her sights on medical school due to her interest in math and chemistry. This was a considerably lofty goal for black women to pursue in the 1940s.

Hopkins became the president of her local Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA).

When telling her aspirations to a fellow white woman member, the woman suggested to Hopkins that she might consider becoming a hairdresser. Hopkins said “I remember thinking, ‘Why would she think I should be a hairdresser? No. I’m not doing that.”

Hopkins’ first choice for higher education was Yale.

Unfortunately, the school wasn’t coed in 1943, so she applied and was accepted to Boston University instead.

She pursued pre-med at Boston University, graduated with a B.A. in Chemistry in 1947, and then applied to BU’s medical school.

Unfortunately, she was rejected due to quotas present that only allowed for two African American student seats, which was filled by a military serviceman and a woman who already had a master’s.

[broadstreet zone=”70106″]

After being rejected from Boston University Medical School, she set her sights on a career in chemistry, a field she was fascinated with since she was young. She then applied to Howard University and eventually received an M.S. in Organic Chemistry in 1949.

After receiving her M.S. from Howard University, she taught chemistry at Virginia State College from 1949 to 1952 before wanting to pursue research. She became an assistant researcher of biophysics at the New England Insitute for Medical Research in 1955 until 1959. She then worked as a chemist at American Cyanamid in Stamford, CT.

While working for American Cyanamid, she finally got accepted into her first choice university, Yale. She got her second M.S. in Chemistry in 1962 and a PhD. in Chemistry in 1967. For her dissertation, she focused on the effects of ADP, a chemical compound necessary for cells to function, in fireflies.

After receiving her Ph.D. from Yale, Hopkins was offered a job as a supervisory research chemist with the Polaroid Corporation in Cambridge, Massachusetts. During her time there, she led the Emulsion Coating and Analysis Laboratory, checking the chemical composition of the coating used for Polaroid’s film strips.

Due to her status as an African-American woman in science, Hopkins eventually attended a conference hosted by the National Science Foundation in 1975. The conference, known as the Double Bind Symposium, was focused on the challenges that people of color, women, and the disabled face and illuminate the underrepresentation in STEM fields.

According to the Martha’s Vineyard Times, Esther Hopkins’ story wasn’t one of overt racial conflict, but one of a more nuanced reality of a black woman in a white, male-dominated academic and professional world in the time before and after the country codified equal rights for all in 1963.

[broadstreet zone=”59948″]

When discussing her expereince at the symposium, Hopkins said “We used to talk about which was more difficult, being a woman or being a minority. I was at a symposium on the subject in 1975 with mostly black and several Asian women who believed that Asians faced greater challenges even than black women. I’ve always thought that it doesn’t matter which is more difficult. You have to deal with both.”

The experience at the Symposium sparked an interest in Hopkins in law.

While working for Polaroid, she attended Suffolk University Law School where she received her J.D. with a concentration in Patent Law in 1976. After leaving Polaroid in 1989, she began work at the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection as the Deputy General Counsel.

Her time as the Deputy General Counsel is what eventually got her to become an elected official in Framingham.

According to Hopkins, “People knew [her] son in Framingham because we lived there and I commuted to work. When I was first decided that I really wanted to apply to be on the Selectboard after we got the strong town manager form of government, moving away from the executive director, and I put my name in and got the interest to do that. At the first meeting when they introduced me, they said I was Tommy Hopkins’ mother and I said ‘I have a name of my own’.

Hopkins then talked about establishing herself as her own person separate from her well-known son, “People greeted me in the grocery store ‘You’re Tommy’s mother!’ and these people all voted for me.”

Hopkins described herself as an introverted person compared to most of her political peers. It took her time to be able to go out and hear stories which she viewed as important because “these people voted for me”.

She also believes that anyone, no matter their personality, can enjoying hearing constituents’ stories.

The connections that she made with the people she elected her helped her to feel that she could go and represent them on the Board of Selectman and provide a voice for people in the town.

When asked about her legacy with the election of Mayor Yvonne Spicer and District 9 City Councilor Tracey Bryant, Hopkins talked about the lack of Black people during the time in which she was elected.

“I don’t think there were that many Black people who were living in Framingham at the time, and I can remember that the Framingham Heart Study did not have Black people who were participating when they first started because the participation was so low. But a few more began to come to the town and I think that looking at the whole Boston area when I was working there, it became more and more diversified as I was there. And certainly, it became more usual to see Black people, and Black people were able to speak up and say the things that they were doing. There were still occasions when people were a little hesitant and didn’t know. Once they understood your background, your questions, your concerns, they listened.”

Hopkins also stressed the importance of not just listening to her own community, but others throughout the city. “I’m not running for a Black seat on the Board. I’m running as a citizen of the community with the idea of my interest being all of the city. You really have to consider everyone.”

[broadstreet zone=”59945″]

She went on to tell about a time when she was a Selectwoman about the importance of this message. “I remember one year when we were doing the budget and the school people were very unhappy with the Board of Selection. We were having our meeting at the town hall and the parents and the teachers and some of the students came into the town hall. We had to keep the meeting room doors open because they were concerned about what we were going to say about the budget. But, the budget was being restricted by Proposition 2 1/2 and by the taxes that were paid by the folks that owned the property. That seemed not the way we should do education, but it’s still the way we do education with property taxes.”

To this day, Esther Hopkins is still being honored for her life-long accomplishments. She is currently a member of the American Chemical Society, and, in 2011, was named an American Chemical Society Fellow. This is an honor only given to about 1,000 members of the nearly 157,000 member society.

Hopkins is also a part of The History Makers – the nation’s largest African-American oral history collection.

She was also honored just this month by the Unitarian Universalist Retired Ministers and Partners Association (UURMaPA) by being awarded the Creative Sageing Award. This award is given to “a member for outstanding service and creativity in pursuing new ventures after retirement, and building on one’s experience in imaginative ways”.

In the press release, the UURMaPA stated that “It will surprise no one, therefore, to learn that after taking early retirement at 63, she began a whole new career in law, plus became very active in local politics and at her church. It is for this latter, varied and diverse activities that UURMaPA awarded her a 2020 Creative Sageing certificate.”