About the op-ed from Framingham History Center Assistant Director Laura Rankin: A year ago, the Framingham History Center presented “Framingham and the Flu: The 1918 Pandemic” featuring former Public Health Nurse Kathleen Hursen and former State Epidemiologist Dr. Alfred DeMaria. During the Q&A Dr. DeMaria was asked if we should expect another pandemic and his response was “not if, but when….” A year before the 1918 flu pandemic broke out, public health nurses and doctors visited households throughout Framingham as part of the groundbreaking Framingham Community Health and Tuberculosis Demonstration. The “TB Study” staff examined every Framingham resident and taught them how to best stop the spread of disease. When the 1918 flu pandemic arrived a year later, Framingham fared better than most communities with one of the lowest death rates in the country. Given the current pandemic, Kathleen wrote the attached article as a public service. It is a reminder about the importance of consistent public health messaging and how when best practices were implemented in 1918 they saved lives in Framingham while other communities that did not heed the messages had a much greater loss of life. The Framingham Community Health and Tuberculosis Demonstration ultimately lead to our community being chosen as the site of the now-famous Framingham Heart Study. At one time Framingham was called “A Health Utopia” – would that we could become that model once again.

***

[broadstreet zone=”51611″]

By Kathleen Hursen. in collaboration with Dr. Alfred DeMaria, Jr.

FRAMINGHAM – Framingham Children’s Health Camp – a fresh air camp for children to fight against infectious disease.

Why did Framingham have the one of the lowest death rates in the country from the 1918 Flu Pandemic?

The answer is found in the historical records at the Framingham History

Center. Let’s look back.

In 1918, Framingham was fighting on three fronts: World War I and the wars against two major disease pandemics, tuberculosis (TB) and the flu. First we’ll start a year before the flu pandemic, when Framingham began to fight the TB pandemic.

In 1916, Framingham was chosen as the site of a landmark study called the Framingham Community Health and the Tuberculosis Demonstration. At the time, TB was one of the leading causes of death and disability. The Demonstration’s task was to develop a public health model that could be used to prevent TB, and reduce the death rate. The Metropolitan Life Insurance Company funded the seven-year project and the pioneering

public health nurse, Lillian Wald, oversaw its implementation.

A Public Health Nurse hopping roofs to reach patients quickly. Courtesy of Visiting Nurse Service of New York.

The Demonstration resulted in a 55% decline in the number of TB cases and a 15% decrease in the death rate. The Framingham Community Health and Tuberculosis Demonstration was called the “crown jewel of the Metropolitan’s health projects” and was adopted around the world. Years later, Framingham was chosen as the site for the Framingham Heart Study in 1948 because of the success of the Demonstration and the

cooperation of the community.

The Demonstration also played a key role in helping Framingham deal with the flu pandemic. By 1918 the project had been providing health services for one year with trained teams of doctors and nurses visiting every household in town. They provided free physical exams and information on how to prevent TB, an infectious disease spread through the air when someone coughs or sneezes. Weekly health letters were posted in

the local paper. Community education on sanitation and disease prevention was provided at the local Civic League.

Residents received a wealth of knowledge on how to stay well and prevent diseases. Massachusetts State Health Commissioner Allen McLaughlin predicted that, “Framingham will be the safest and healthiest spot on the face of the earth.”

When the 1918 flu pandemic hit Framingham, most residents were well aware of how airborne diseases like TB and the flu were spread and how to protect themselves. Because they knew and trusted the doctors and nurses who had been in their homes, they followed the advice of the medical and public health experts.

Like today’s coronavirus pandemic, the flu pandemic created a major public health emergency.

Framingham hospitals were so overwhelmed there was a shortage of beds.

Tents were set up, and even the nurses’ lodgings were used to care for patients. There were shortages of doctors and nurses, as many had been drafted into the war or were sick themselves with the flu. So all available doctors and nurses were recruited to assist and routine visits and clinics were suspended. Like today, the health department closely monitored the outbreak. Doctors and nurses were mandated to report all cases and their

status.

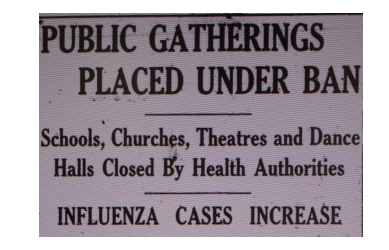

All public gathering places were closed for weeks. Schools, churches, theatres, dance halls, bowling alleys, and the Civic League were forced to close. All meetings were banned.

Residents were instructed to go outside into the fresh air and walk, rather than use trains and trolleys.

Public health nurses visited every household twice to teach residents how to protect themselves from the flu and what to do if they became sick. Nurses and doctors frequently made house calls to residents sick at home and those at high risk like the elderly and those with chronic medical conditions. The townspeople were well informed because the public health officials gave consistent messages. Those who were sick were instructed to remain home.

[broadstreet zone=”53820″]

The Demonstration project was forced to switch gears and focus on the flu. They posted frequent health letters in the newspaper to reinforce important health messages and they also donated medical equipment to the hospitals and health departments.

There were major outbreaks among the soldiers who were often housed in close quarters in barracks. Sadly a large number of soldiers who survived the war died from the flu.

Three thousand sailors were sent to the military camp at the Musterfield in Framingham, to be separated from the outbreak in Boston. Not one sailor at the camp became sick with the flu.

The highest death rates from the flu pandemic occurred in cities and towns that ignored public health warnings and allowed the public to congregate. Gathering places remained open and parades celebrating the end of World War I took place.

The Framingham community came together to help in creative ways. Food deliveries were set up for residents and hospitals. Volunteers prepared food using the kitchens at Framingham High School and Framingham Normal School now Framingham State University. Cots and blankets were donated to the hospitals by the townspeople. Many teachers volunteered to help the hospitals.

In 1918, Framingham developed important public health protective measures that resulted in the dramatic reduction in the flu death rate, its transmission and business lockdowns.

Today, many public health programs are using the same protective measures and education programs to stem the rapid spread of the coronavirus.

Although we are in a tough situation now, what we learned from the past is helping us to make the right decisions today.

***

This article was compiled from research gathered by the author for “Framingham and the Flu: The 1918 Pandemic” at the Framingham History Center on March, 23, 2019.

Kathleen Hursen, RN, MS former Public Health Nurse for the Town of Framingham (1989-1995) and Director of Education and Training at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health Division of TB Prevention and Control.

Dr. Alfred DeMaria served as the Massachusetts State Epidemiologist from 1990-2018 and continues to provide consultation to the Bureau of Infectious Disease Prevention, Response and Services in the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Dr. DeMaria is on the Board of Directors of the Public Health Museum – publichealthmuseum.org